If a student walked off the Harvard campus and onto the street in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and argued in favor of the genocide of Jews, the US Constitution would prevent her from being prosecuted for hate speech.

If the same student left her spot on the sidewalk and returned to Harvard’s campus to continue the rant, the student could be silenced by campus police and suspended or expelled from the university under the school’s code of conduct.

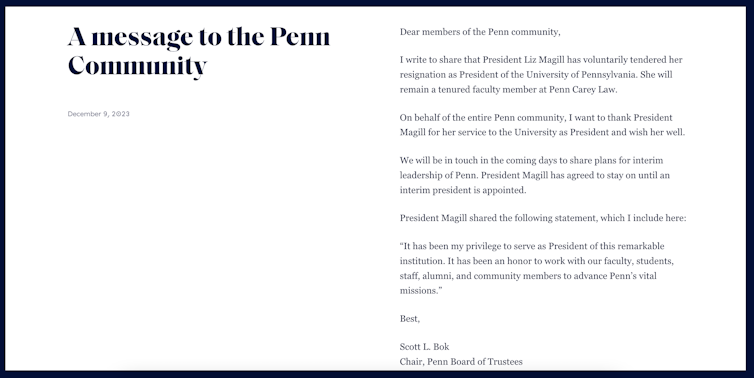

The same is true for many other universities across the country, including the University of Pennsylvania and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Private colleges and universities have speech codes that allow them to penalize certain speech. But in their December 6, 2023 testimony before Congress about anti-Semitism on their campuses, presidents Elizabeth Magill of the University of Pennsylvania, Sally Kornbluth of MIT, and Claudine Guy of Harvard failed to state it clearly, when U.S. Rep. Elise Stefanik pressed them to explain what It is happening. It would happen if someone on campus called for the genocide of the Jews. Magill has just resigned, largely because of the uproar that followed.

I have taught undergraduate arguments and First Amendment law for 15 years at Syracuse University and wrote a user’s guide on the First Amendment: When Liberty Speaks.

I’m surprised the bosses failed to respond clearly to Stefanik’s question. The primary purpose of schools is education. Private colleges and universities are subject to a code of conduct that supports and implements this goal.

Although private colleges and universities can, and often attempt, to recreate the broad boundaries of protected expression provided by the First Amendment, these boundaries can be legally narrowed by their educational mission. They do so because hate can poison a healthy learning environment and impair the ability of targeted students to fully participate.

Public colleges generally must apply broader constitutional standards regarding campus expression. But campus laws at private colleges and universities seek to resolve the conflict between the right to speak freely and the educational mission of the institution. The clumsy and over-the-top responses by the three university presidents show how this attempt to balance expression and safety can create confusion, conflict, and the opportunity to make selective enforcement decisions based on academic fashion, not the values of free and open debate.

AFP Photo/Yuki Iwamura, file

special restrictions; Public freedom of expression

Words matter. As long as the words do not include a realistic threat that sticks, stones, and worse will soon come, the First Amendment protects them from government oppression.

Constitutionally, ideas—whether mainstream or contemptible—that do not incite violence or intentionally intimidate the target are considered permissible speech. The First Amendment requires that such ideas be available to the public to examine and criticize. Neither states nor the federal government can prosecute exaggerated hate speech, even speech that endorses genocide or advocates forced racial and ethnic division, criminally. These words may be insulting and intimidating, but they are often an integral part of emotionally charged political discourse.

Harvard University provides an example of how campus codes of conduct restrict speech that would normally be permitted under the First Amendment. The student handbook states that the free exchange of ideas should take place within “the limits of reasoned opposition.” The First Amendment requires no such restrictions on free speech, and state and federal governments are constitutionally prohibited from creating or enforcing any such obligations.

The University of Pennsylvania Code of Conduct requires members of its community to “respect the health and safety of others.” However, under the First Amendment, state and federal governments are constitutionally prohibited from imposing such restrictions.

MIT prohibits harassment, which is defined as “public and personal speech.” The First Amendment provides no such moral guidelines. He does not differentiate between truth or lies, myth or reality, virtue or evil. It only creates a space for speech where the government has limited power to intervene.

Youpin website

Selective enforcement?

However, despite the universities’ own codes of conduct, there is a growing perception – supported by the qualified and highly technical answers given by college presidents at the hearing – that they and other colleges and universities are selective in applying codes of conduct and using them to further a political agenda.

In situations involving race and gender, schools have been quick to warn against, curb, or punish speech that administrators consider offensive. In 2017, Harvard University rescinded admission offers to 10 students who posted sexually explicit images, some targeting minorities. In a Wall Street Journal op-ed, Stefanik wrote that in 2022, as part of mandatory anti-bias training, Harvard warned its undergraduates that sexism, fatphobia, and using the wrong pronouns are offensive.

In 2016, several colleges issued proposed guidelines on offensive Halloween costumes. In 2013, two students at Lewis & Clark College were accused of discrimination or harassment for hosting a racially themed private party. In 2006, the University of Wisconsin attempted to limit the printing of a satirical article that the administration deemed a threat to the recruitment and retention of students from underrepresented groups, although this decision was later overturned.

In contrast, Jewish students at the three universities whose presidents testified in Congress accuse their schools of failing to provide a clear response to the alleged repeated harassment of Jewish students and staff.

Defenders of free speech on campus

But rather than punishing specific speech, others are calling on colleges and universities to uphold the principle behind First Amendment freedoms: more expression, not less, leads to a healthy democracy.

Proponents of strong protections for campus speech argue that rules that limit speech to polite dialogue stifle the ability to recognize different viewpoints and truths, which sometimes find expression only in heated diatribes. Instead, they suggest that in addition to clear condemnation, educational institutions should respond to hate speech through counter-messaging and dialogue as well as support for targeted individuals and groups.

Many of today’s students do not understand or respect the campus—and thus democracy—where all ideas are subject to scrutiny, especially those they hate. To me, the data is alarming:

- 46% of students support booing speakers they disagree with.

- 51% of students believe that discussion of certain topics should be prohibited on campus.

- 45% of students believe physical violence is justified in response to hate speech.

PEN America, a 100-year-old organization dedicated to celebrating and protecting creative expression, urges colleges and universities to exercise caution when trying to balance expression with safety.

Others warn that the code of conduct provides a false sense of security for targeted students. Their point: Unless such rules are carefully crafted and applied only to speech that creates physical harm or terror, they will succeed mainly in pushing hate underground into echo chambers, where it tends to become more extreme and more dangerous.

University presidents across the nation are facing a unique and challenging dilemma when it comes to punishing individuals who call for genocide on college campuses. The issue stems from the complex web of free speech laws and protections on these institutions, which are both more and less strict than the First Amendment. While university leaders are committed to fostering an environment of open dialogue and diverse perspectives, the rise of hate speech and calls for violence presents a moral and legal quandary that requires careful navigation. In this essay, we will explore the difficulties that university presidents encounter when attempting to address and discipline individuals who promote genocide, all within the context of the complex free speech landscape of college campuses.