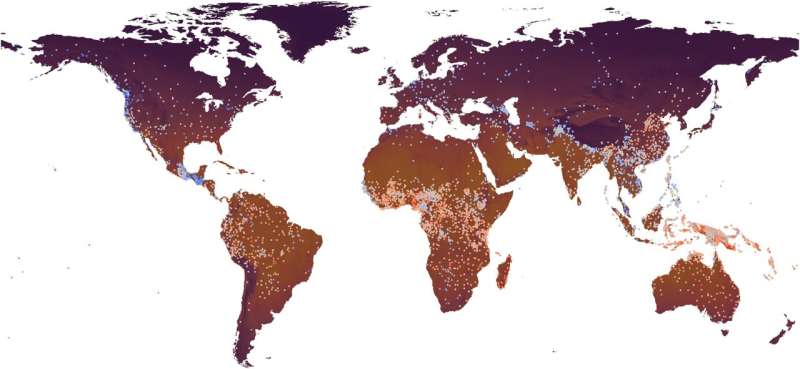

Global distribution of mean sound indices (MSIs) across 9179 linguistic types from the ASJP database. The color of the dots represents the MSI of the language, where red dots indicate higher indices and blue dots indicate lower indices. The fill color of land areas represents the average annual temperature. credit: PNAS Association (2023). https://doi.org/10.1093/pnasnexus/pgad384

Languages are a major factor in human societies. It connects people and serves as a means of transmitting knowledge and ideas, but it also distinguishes between different groups of people. Languages can therefore tell us a lot about the societies that use them. Since languages are constantly changing, it is important to know what factors play a role in this. Scientists can then reconstruct past processes based on languages.

In a study published today (December 5) in the electronic journal PNAS AssociationLinguist at the University of Kiel, Dr. Soren Wichmann, together with colleagues from China, explain that average ambient temperatures affect the loudness of some speech sounds. “In general, languages in warmer regions are louder than those in colder regions,” says Dr. Wichman.

Air physics affects speech and hearing

The basic idea behind the study is that we are surrounded by air when we speak and listen. Spoken words travel through the air in the form of sound waves. The physical properties of the air therefore affect how easily speech is produced and heard.

“On the one hand, the dryness of cold air poses a challenge to the production of vocal sounds, which require vibration of the vocal cords. On the other hand, warm air tends to dampen non-vocal sounds by absorbing their high-frequency energy.” Dr. Wichman explains.

These factors can favor the loudness of certain sounds in warmer climates, which is known as acoustic in scientific terms.

An extensive speech database aids in analysis

Dr. Wichman and his colleagues used the Automated Similarity Judgment Program (ASJP) database to test whether these factors actually have an impact on the evolution of languages. It currently contains the core vocabulary for 5,293 languages and is constantly being expanded with support from the ROOTS Cluster of Excellence.

Dr. Wichmann and his colleagues found that languages spoken around the equator in particular have a high average pitch, while languages in Oceania and Africa have a similar highest index. In contrast, the world record for low pitch goes back to the Salish languages found on the northwest coast of North America.

However, there are some exceptions to this trend. For example, some languages in Central America and mainland Southeast Asia have a fairly low average pitch, even though they are spoken in very warm regions.

“In general, however, we were able to establish a clear relationship between the average phoneme in language families and the average annual temperature,” emphasizes Dr. Wichmann. The exceptions are that the effects of temperature on sound develop only slowly and only shape language sounds over centuries or even millennia.

New research approaches to the phenomena of human societies

Scientists are currently intensely debating the extent to which environment influences the formation of languages. “For a long time, research has assumed that language structures are autonomous and in no way influenced by the social or natural environment. Recent studies, including ours, have begun to question this,” says Dr. Wichman.

Such studies can also open new paths to insights into human societies, for example on the topic of migration. “If languages adapt to their environment in a slow process lasting thousands of years, then they hold some clues about the environment of their predecessors,” says the Kiel-based linguist.

more information:

Tianheng Wang et al., Temperature shaping language sound: revalidation on a large data set. PNAS Association (2023). doi: 10.1093/pnasnexus/pgad384

Provided by Keele University

the quote: Linguistics study claims languages are louder in the tropics (2023, December 5) Retrieved December 12, 2023 from https://phys.org/news/2023-12-linguistics-languages-louder-tropics.html

This document is subject to copyright. Notwithstanding any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for informational purposes only.

The study of linguistics has long been fascinated with the idea that languages may be more vibrant and expressive in tropical regions. This theory suggests that the rich diversity of flora, fauna, and natural landscape in the tropics drives individuals to develop more complex and nuanced communication systems. Linguists have proposed that the abundance of stimuli and environmental challenges in these regions may have shaped the development of language in such a way that makes it more vivid and demonstrative. In this essay, we will explore the evidence and arguments behind this claim and consider its implications for our understanding of language and culture.